Hey everyone. I’m Jim “Apothis” McArdle, the head of strategy for R&D at Riot. In this post we’re going to talk about the strategic foundations we look for in a game project, why they’re important, how to define them, and how to make sure you keep them in mind as you develop your game.

A major lesson we’ve learned over our years of doing R&D is the importance of building on the right foundations. Because our work starts from an idea, it’s important to do things in the right order, and ensure you’re building houses on firm foundations, rather than castles in the sky.

One of the most important foundations is clarity on your Opportunity (capital “O” to avoid confusion), Thesis, and Audience. These are essential to ensuring team alignment around “what you’re trying to do” and “who you’re doing it for,” focusing the scope of your innovation so you can work on what matters and ignore what doesn’t, and having a way to validate that you’re making progress towards your goal.

We’ve seen teams struggle or fail for a multitude of reasons, but many of them came down to ambiguity or poor decisions regarding what they were trying to do, why, and for whom.

Defining Opportunity, Thesis, and Audience is the major activity of our Incubation phase—the first phase of development where we establish the foundations of the team’s strategy, direction, and leadership, before we even start writing code.

So what does good looks when we’re defining our Opportunity, Thesis, and Audience?

Opportunity

An Opportunity is an (unserved) audience, (under-realized) product, or (disruptable) market that you want to pursue, usually one you can associate with a high level market size and audience. A promising Opportunity diagnosis usually includes some insight into an untapped audience or valuable innovation. It’s not prescriptive about how you’ll address the opportunity, but it focuses the high level “product strategy” on the outcomes you want to achieve. It answers large questions like level of innovation / general innovation space, regional / demographic audience targets, platforms, etc. An example of an opportunity is “bring Lego into the gaming space” (Minecraft) or “adapt DOTA into an online, social, games-as-a-service paradigm” (League of Legends).

Broadly, I would say there are two common approaches to opportunities: inside-out and outside-in.

Inside-out opportunities start from an existing product / design loop that you believe could reach a larger audience with thoughtful improvements. Some examples of opportunities like this are DOTA > League, Everquest > World of Warcraft, and King of the Kill > PUBG / Fortnite.

The required insight here is usually into why the product is compelling and what problems need to be solved to expand the genre. We love opportunities like this because you’re starting from something you know has promise, so you can focus innovation on the key aspects that will really take the experience to the next level.

Outside-in opportunities start from an untapped market or audience need. These tend to be more “blue ocean.” They’re harder to pursue because there’s a ton of innovation scope to be addressed in resolving what a good product looks like. There are lots of clever ways of approaching this, like looking for analogies from other product spaces. For example, if you thought there was a large unmet need for a video game that allows young people to express their creativity, you might look at other products that do that, like Legos, and then try to make a gaming equivalent.

Thesis

Thesis is where we define how we’ll address the Opportunity. A good thesis lays a thoughtful diagnosis of the problems / opportunities inherent in the Opportunity, solutions for those problems or approaches to capitalizing on those opportunities (which will often be the key pillars of your proposed game), and an articulation of why solving those problems or realizing those opportunities has the potential to be a huge game worth pursuing.

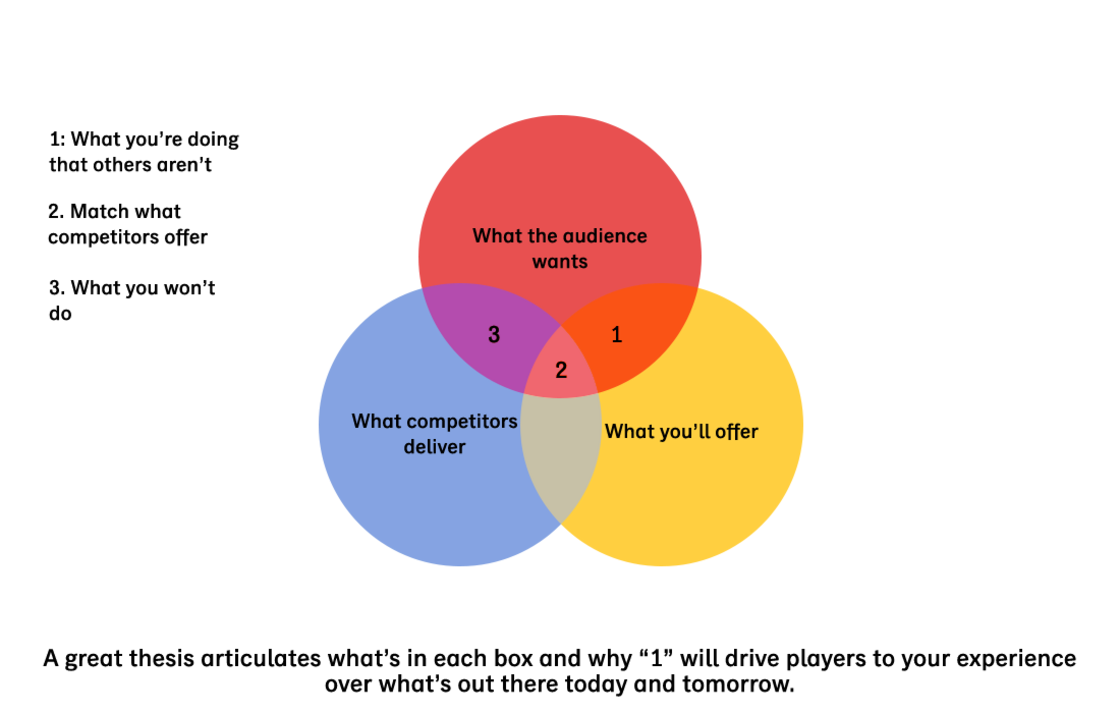

A good thesis explains what’s different or better about your game that audiences want and your competitors don’t or can’t offer. It also makes it clear what you’re NOT going to do, helping the development team achieve focus on what matters. For bonus points, a great thesis articulates why your competitive position will be defensible over time against future market entrants.

Your Thesis should articulate what the core innovation areas of your game are and any other key risks or assumptions related to the success of the product. Knowing what your important and complex innovations are is critical to building your plan for the Prototype phase. We won’t dive deeply into milestone-driven development here, but the core idea in our design is that in the Prototype phase you want to de-risk the areas of innovation in your game that are critical to success in the most efficient and quickest way possible.

Audience

The last element of this foundation is an understanding & prioritization of the audiences for your game, which serves two major purposes. First, an understanding of your audience helps you better tailor numerous strategy, design, and operational decisions. Second, if you know who your intended audience is, you can find those people and playtest with them to inform your development and validate your progress.

A strong audience definition has several aspects. We typically use 3-5 prioritized segments generated by the game team in collaboration with Strategic Advisory. A segment is usually defined by a set of needs (emotional or functional) the audience wants satisfied by a product, any important behavioral context or constraints (i.e. solo vs group play, location, amount of time to play, the platform they’re using, etc.) that define how the product best fits into their lives, and a set of gaming experiences that are currently, at least partially meeting their needs and constraints.

Next, you want to define what they really like about the games they’re playing today as well as what those games lack that players want. It can be helpful to round this out with some more descriptive information like regions, demographics, etc.

Lastly, you want to understand the size of each segment (both overall and how many you think are likely to play your game) so you can develop a sense of priority. Understanding the size and priority of your audiences is key to making thoughtful trade-offs when you can’t satisfy everyone, whether it’s because of their needs from the design conflict or because your resources are limited. Combining this sizing information with how well we think we can attract players into the game lets us typically generate three groups:

- Core audience: Players who definitely should love your game

- Growth audience: Players who could be attracted into this game if we make the right decisions

- Breakout audience: Players who’ll be incidentally attracted in small or large numbers depending on if we have a hit

Conclusion

When you bring all of this together you should have a clear, rigorous, and “lean” (lacking unnecessary bloat) hypothesis for how to make a successful game—something that a large number of players will choose over existing experiences and that can achieve durable success.

It should be evident what gap in the market you’re capitalizing on, what major innovations or improvements you’ll bring to the space, and why that will make a large audience want to engage with your game. We don't require teams to start with ALL of this from the very get-go. You can start from any place including things not on the list (like I'm personally inspired by this game), it just all has to be explainable eventually. As you continue in development, it’s critical that you keep this understanding up to date as the market changes, your understanding of your audience improves, or you learn more about how your product fits (or doesn’t fit) your audience's needs and that you maintain team alignment around this evolving hypothesis.

Operationally, it’s important to ensure that your team, especially leadership, is aligned on this understanding, and that your new team members are onboarded with this in mind. This way your team can maintain this alignment as your hypotheses evolve. If you’ve been in development for a while but haven’t done this exercise yet, it usually involves a lot of sharp choices, collapsing a broad possibility space to a more specific target, and you may find that this isn’t the game some people have in mind. There will be meaningful work to agree on the more specific direction, or personnel may have to change. This can be painful, but alignment on these fundamentals is critical if you want to have a fast moving AND democratic team. Otherwise you may find yourself mired in intractable debates about feature specifics that are difficult to resolve because folks aren’t already on the same page about foundational assumptions.

This may seem like a lot of effort spent on thinking, researching, hypothesizing, and aligning when you could be building and testing. That bias to action is a great instinct! It’s deeply valuable in the best prototypers, but it’s hard to oversell the value of laying strong foundations with an understanding of Opportunity, Thesis, and Audience.

Good theories here don’t just expedite team decision making, they increase the likelihood you're making something players actually want, and they’re the difference between naive exploration and hypothesis-driven development. Ultimately, our experience has been that the best teams have a crystal clear understanding of who they’re making their game for and why it’s better for those players than existing offerings. They constantly improve and refine that understanding as they get new information, and that understanding is consistently reflected in the decisions they make.

Jim "Apothis" McArdle

Jim "Apothis" McArdle is Head of Strategy for R&D at Riot. He previously led Insights for Valorant and Riot's platform initiative. He used to travel around the world learning languages, cooking, and doing adventure sports... until he took an arrow in the knee and moved to Los Angeles to work in technology and gaming. Jim holds a BA from Cornell University where he studied Economics, Psychology, and a splash of Physics.